In Search of a Mission: Reflections on the Museum of World Culture and Ethnography in the 21st Century

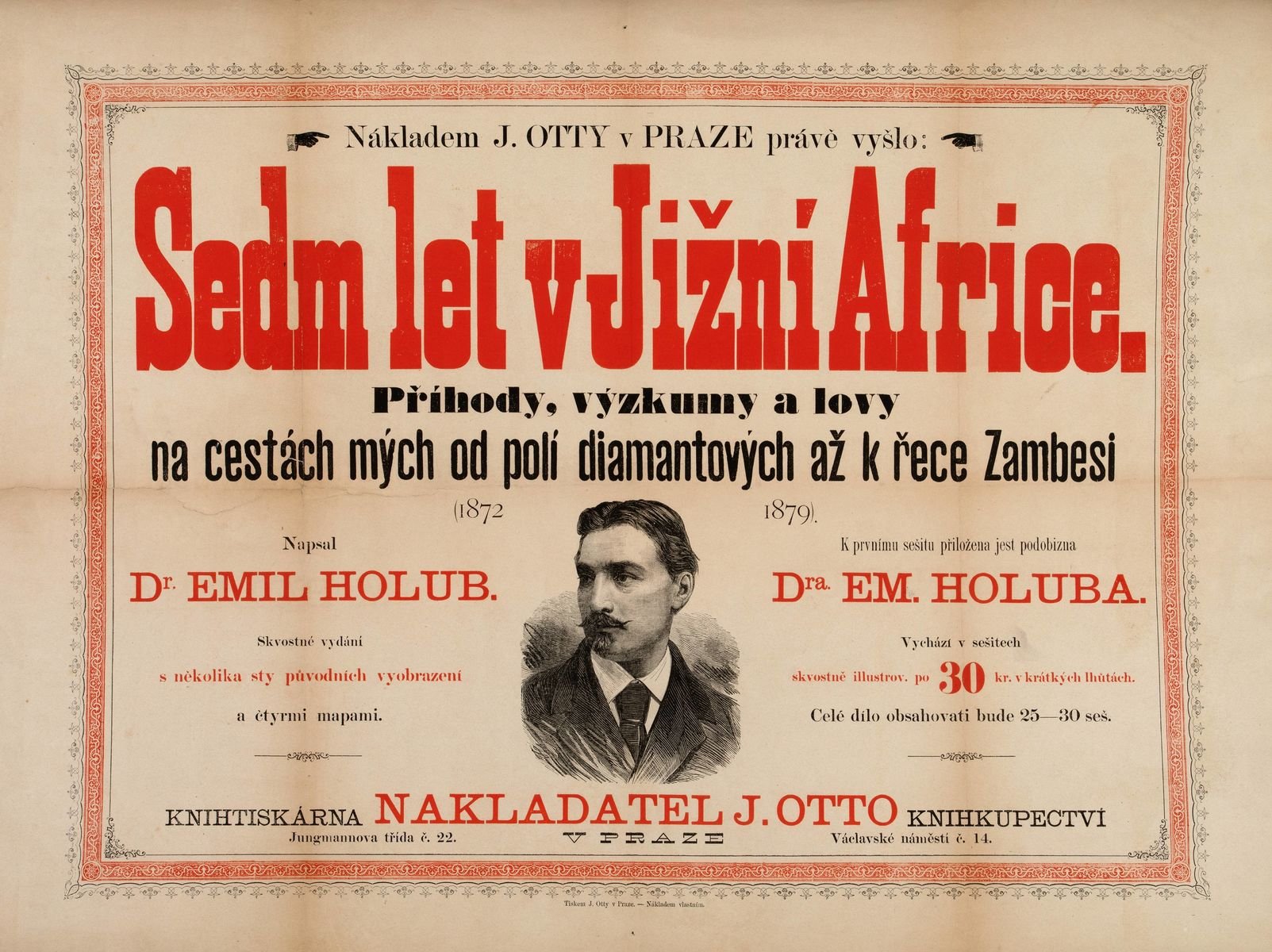

When the exhibition on Emil Holub (1847–1902) opened at the Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures in Prague in April 2023 (Figure 1), it was a courageous attempt to view in a more critical way the activities of one of the most celebrated figures in Czech culture of the late nineteenth century. Holub is still lauded across the Czech Republic, in school textbooks, magazines and popular publications, as the Czech ‘David Livingstone,’ the explorer who shared his experiences of southern Africa with the Czech and Austrian publics. Yet just as Livingstone and other imperial figures have come under increasing scrutiny in recent years in Britain, the exhibition in Prague suggested that it was time to undertake a similar examination of Holub’s record.

Holub was not, of course, colonizing the continent, yet questions are increasingly being asked about his ethics; he does not appear to have gained anyone’s permission when he collected thousands of artefacts, including, most notably, a series of rock carvings. Markéta Křížová has recently emphasized that Holub believed he was ‘saving’ them.[1] But even if he was sincere, this was in a colonial context when European explorers routinely helped themselves to the artefacts of other cultures. His memoir, Seven Years in South Africa (Figure 2), which was published in numerous languages, made clear why he felt entitled to do so. Africans were, he argued, savage, child-like, primitives who were not able to manage their own affairs.[2]

Most of the rock carvings are now in the Weltmuseum in Vienna, but Holub donated many other items he collected to the Náprstek Museum, where they are still kept. Consequently, the exhibition not only raised questions about Holub, but also about the museum itself, which has benefitted from numerous donations that have a similarly questionable provenance.

Museums of non-European art and culture have become the object of considerable critical attention in recent years, as have the collectors that donated to them. As the circumstances under which their collections were amassed have been increasingly investigated, it is now generally argued that they were part of the apparatus of colonialism. In the most extreme cases, many collections in such institutions can be accurately described as the spoils of colonial conquest. The Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, for example, has artworks and artefacts that were transported to France following the Franco-Dahomean wars of the 1870s, while the former Museum of Mankind (now part of the British Museum in London) has the extensive collection of bronzes from Benin that were pillaged after the expeditionary war of 1897 by the British army. Disputes over the return of artefacts reached a high point recently with the opening of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin in 2020, combining the collections of the city’s former Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Asian Art. In a climate when there had been growing calls for the restitution of collections to their countries of origin, the Forum was criticized for its lack of research into the provenance of the artefacts on display. At the very least, they had made their way to Berlin at the same time that the German state was embarking on a project of colonial expansion in Africa and Oceania, a coincidence that suggests the need for some investigation.[3]

There was no overseas Czech empire, but the Náprstek Museum and other galleries and museums across the Czech Republic have collections of art from outside of Europe, the provenance of which has yet to be examined properly. One of the reasons for this lack of research is a reluctance to accept that Czechs (and Slovaks), too, may have been involved in the European colonial project. In addition, it is often a matter of local and national pride that individual Czechs gained recognition on the global stage. Hence, in addition to a national institution such as the Náprstek, there is a string of museums in smaller towns marking the achievements of local travellers and collectors. The Alois Musil in Vyškov, for example, celebrates the eponymous oriental scholar, and, in Humpolec, the Hrdlička Museum commemorates the achievements of the physical anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička, while the municipal museum in Moravská Třebová proudly displays the collections of Indian and ancient Egyptian objects acquire by the local entrepreneur Ludwig Holzmaister. A more distanced view towards the activities of these individuals has seldom been articulated, since they are so bound up with the affirmation of modern Czech nationhood as well as local municipal identities. Consequently, where Czech scholars have undertaken critical analysis of ethnographic collections, the examples chosen are usually those in Western Europe, based on the tacit assumption that it does not apply to museums in Central Europe.[4]

Considerable work thus remains to be done on the history and provenance of such collections in the Czech Republic. This is not to suggest that they are all the result of secondary colonial plunder (i.e. looted objects acquired indirectly on the open market). Indeed, it is important to remain open to the possibility that many works of global art were genuine gifts to travellers and explorers, or were sold and exchanged under conditions entirely free of coercion. Nevertheless, the more critical study of donors and collectors is still underdeveloped. In this respect, he Holub exhibition in Prague remains a rarity.

Yet rather than merely dwelling on the origins of collections, it is just as important to consider how global art and artefacts are displayed in museums. Some museums have sought explicitly to address their problematic roots. In Leiden, in the Netherlands, for example, the World Museum (Wereldmuseum), previously known as the Museum of Ethnography (Museum Volkenkunde) openly admits that its collections (Figure 3) are the result of the centuries of Dutch colonial enterprise. Likewise, the Weltmuseum in Vienna, formerly the Museum of Ethnology, has also embarked on a process of making transparent the circumstances under which its various collections, including, most famously, the so-called headdress of Moctezuma II (Figure 4), the last ruler of the Aztecs, ended up in Austria.

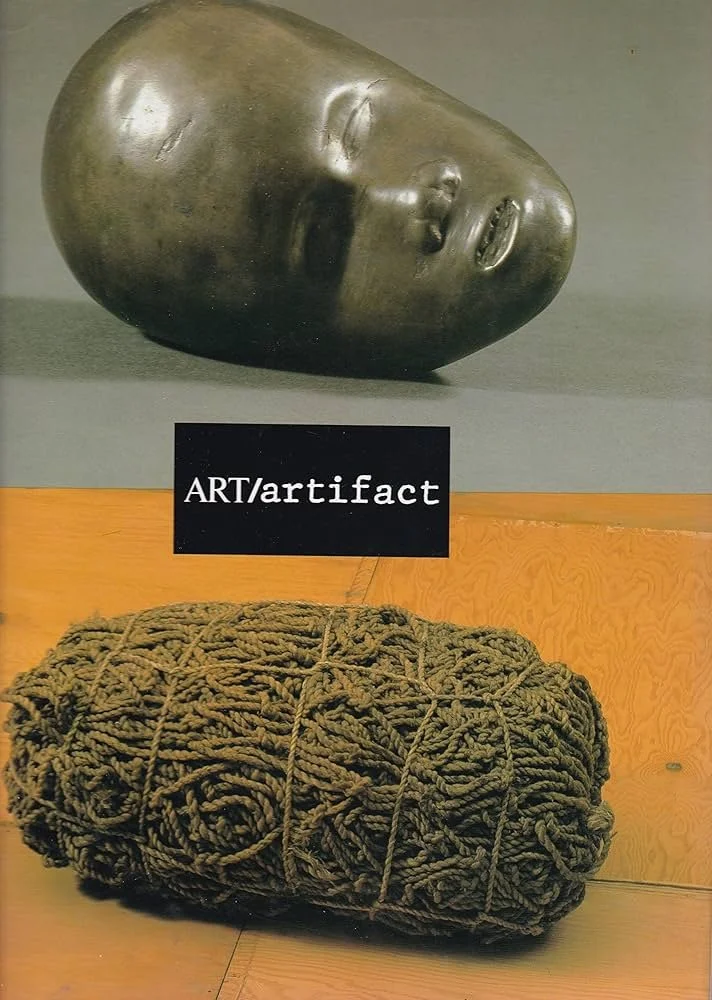

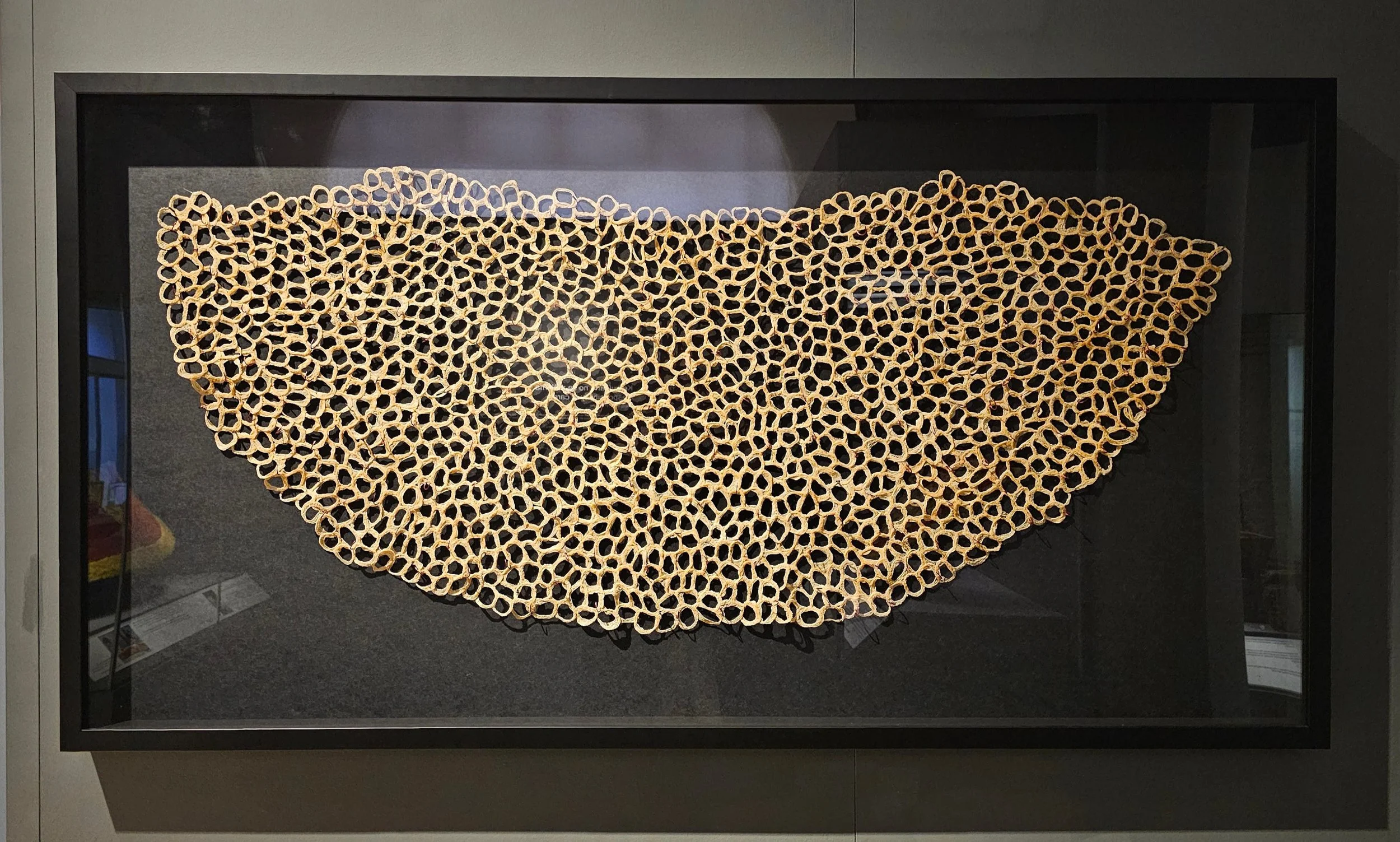

The renaming of these institutions, which were all originally ethnographic museums or collections, reflects the unease at the very practice of having a specific class of institution dedicated to the art and material culture of Asia, Africa, Oceania. The idea of classifying Sepik masks or Baule sculptures, for example, as ethnographic artefacts betrays the legacy of western academic disciplines that drew arbitrary lines between different cultures. A Baule mask is categorized as an artefact, whereas a mask worn in the context of classical Athenian drama is a work of art, even though both had a place in a religious ritual. This distinction has been a recurrent subject of debate. The now famous exhibition Art/Artifact staged at the Center for African Art, New York, in 1989, examined the ways in which techniques of display could also determine whether an object was viewed as a work of art or as an artefact.[5] As the philosopher Arthur Danto argued, the Zande net (Figure 5) from West Africa illustrated on the front cover of the exhibition catalogue could, under the right exhibitionary conditions, be understood to be a work of minimalist art rather than a functional object.[6]

The division into (western) artwork and (non-western) artefact is entrenched everywhere, including in the Czech Republic, where objects are displayed as ‘specimens’ and where exhibits from the same culture and geographical region, as well as social purpose (Figure 6), are all displayed together. Might it therefore be easier simply to relabel masks, weapons, and other objects as works of art? Clearly, they have many aesthetic qualities, and the Quai Branly has chosen to display its collections with carefully placed lighting (Figure 7) in order to bring out their artistic character. Yet this is just as misleading. It is not wrong to admire them as objects of astonishing beauty, but this is not the same as regarding them as works of art. There has been no shortage of criticism of the aestheticization of objects, which removes them from their context of use and meaning. For, as the American philosopher Kendall Walton argued in a famous essay, ‘On Categories,’ published nearly 60 years ago, if we misunderstand what kind of an object we are looking at, we may equally make fundamental errors in deciding which aspects of it even merit special aesthetic attention.[7] It has also long been objected that the concept of ‘work of art’ (ie an object or image produce primarily for aesthetic enjoyment) is not universal. It appears in certain cultures, including classical and post-Renaissance Europe, China or Japan, for example, but in many other cultures it is difficult to disentangle aesthetic from other values, such as magic, religion, or even functional purpose.

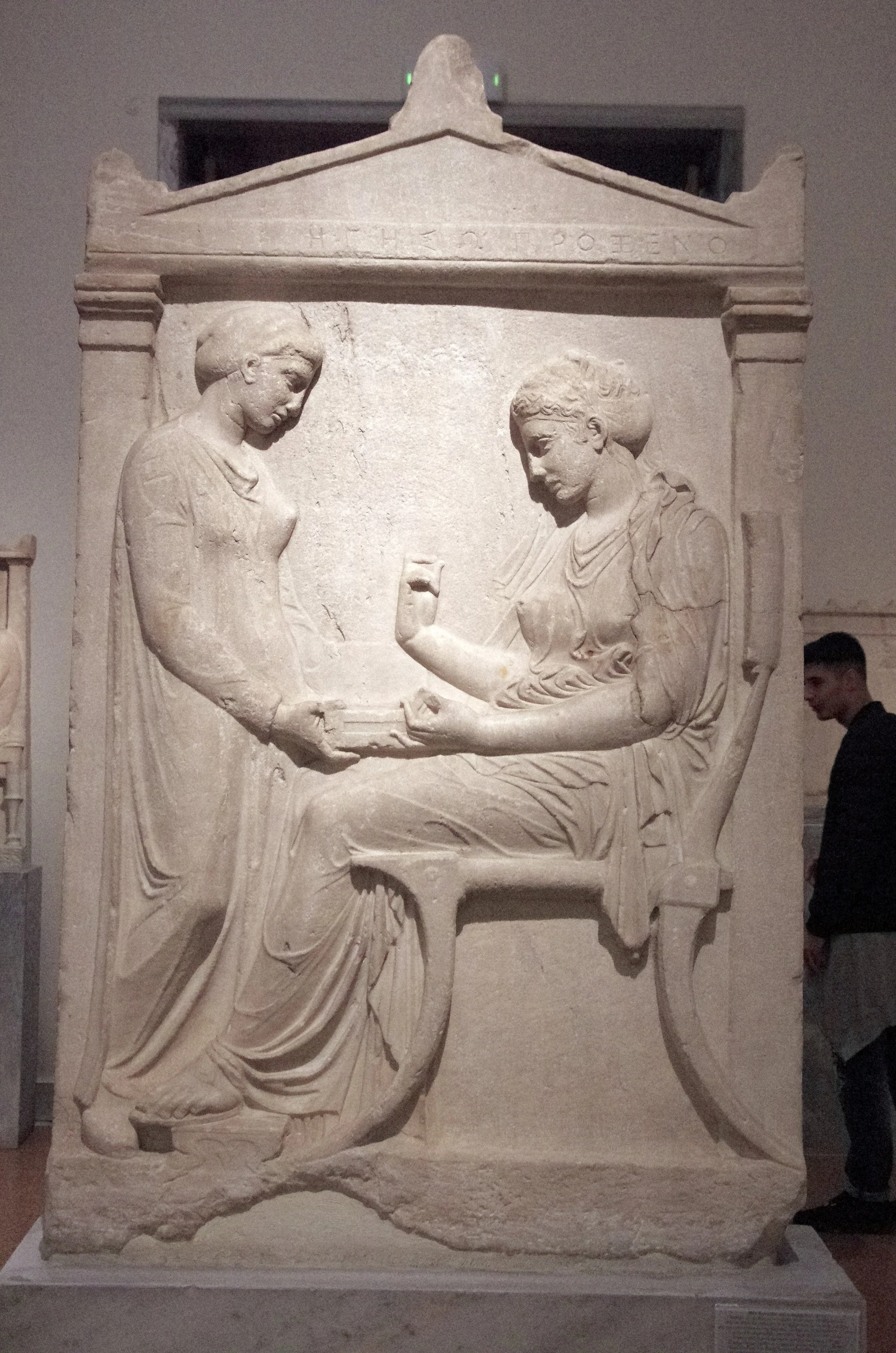

A more promising alternative to this division might be to view western artworks as themselves ethnographic artefacts. If grave markers and altars from Oceania can be displayed by the Quai Branly (Figure 8) as indicators of funereal practices, then equally, perhaps, an object such as the fifth-century BCE grave stele of Hegeso (Figure 9) attributed to the Athenian sculptor Callimachus might be ranged alongside them as an ethnographic specimen rather than as a work of art. Many scholars have done precisely this; the German classical scholar Walter Burkert, for example, published a number of highly influential studies on the anthropology of ancient Greek religion.[8] Such works have had limited impact on museum practice, though; in Paris, classical works of art are still displayed in the Louvre whereas those from Africa are in the Quai Branly. This is replicated in Prague’s National Museum, where antiquities and artworks from the ‘high cultures’ of Asia (e.g. China, Japan, Tibet, and the Islamic world) are kept separate from the ethnographic collections. This stems from the fact that even if generations of western scholars – including Czechs - regarded Islamic or Chinese art, for example, as less developed than that of Europe, they still recognized it as art. The same privilege was not extended to much of Africa, Oceania, or the native cultures of North America. No matter how much collectors admired their material culture (Vojtěch Náprstek, for example, was an enthusiast of the native Americans he encountered), such regions were still held to belong to a different category of culture.

These are commonplace observations, perhaps, but no less important since they highlight not only the limitations of museological practice, but also the challenges museums face. They have to organize their collections in one way or another, and no matter how inventive they may be, the choices they make rule out some possibilities just as they enable others. Institutional inertia plays a role, too; while museums cannot continually reorganize their collections in radical ways, temporary exhibitions need not pose such barriers. Yet the boundary between art history and ethnography is seldom breached, and this maps onto the difference between the presentation of the art of the ‘high cultures’ of Europe and Asia with that of much of the rest of the globe. Even though, as the American anthropologist Shelly Errington argued, ‘authentic’ primitive art disappeared decades ago, with a globalized artworld that has seemingly erased earlier categorial differences, many museums still tacitly operate as if this were not the case.[9]

An instructive example I was able to visit in November was Fault Lines: Imagining Indigenous Futures for Colonial Collections, a temporary exhibition staged throughout 2025 at the Museum of Anthropology & Archaeology in Cambridge.[10] This is not an insignificant venue for the present discussion. Not only was the University of Cambridge one of the leading centres of anthropology in the English-speaking world in the early twentieth century, it was also home of the so-called Cambridge Ritualists, classical scholars such as Jane Harrison, George Thomson and Gilbert Murray, who viewed ancient Greek culture through an anthropological lens.

In many respects the permanent display typifies the traditional European ethnographic museum: a spectacular arrangement (Figure 10) of large objects, such as totem poles and canoes interspersed with wooden cabinets of tools, weapons, ritual masks, items of clothing and jewelry, all organized by geographical region. There is a self-consciousness to this in Cambridge, for it makes the historical practices of ethnographic display themselves into an exhibitionary object. This approach occurs in a number of other museums; in Madrid, for example, a small gallery of the Museum of America displays early pre-Columbian items in a recreated cabinet of curiosities, highlighting how they would have originally been seen in sixteenth-century Europe. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford has deliberately preserved the original format of the displays, in a visual spectacle (Figure 11), that includes objects such as shrunken human heads that many would regard as transgressing curatorial ethics.

Yet alongside the preserved historic arrangement of the permanent collection in Cambridge, Fault Lines, an inquiry into ethnographic collections, explores alternative models of presentation. Some of the exhibits are historic objects collected decades ago, such as the feathered cape (‘ahu’ula) (Figure 12) acquired in 1947. Others are by contemporary makers, such as Ho‘oheihei (Figure 13) by Kalupani Landgraf from Hawaii, or Syuwenulh, S’ulxwé:n, Snuw’eyulh by Atheana Picha (Figure 14), a Salish maker from the Kwantlen First Nation. In keeping with current best practice guidelines, indigenous makers have, wherever possible, been consulted in the arrangement and curation of the exhibits, and they have also provided accompanying explanatory statements about their work. I deliberately avoid referring to them as ‘artists’ since the exhibits occupy an ambiguous space between art and artefact.

Anthropologists have long debated the pitfalls of imposing the vocabulary and concepts of European inquiry on other cultures, and the curators have consciously taken this to heart. Indigenous concepts and names are given priority, and the visitor is presented with a baffling array of terms and names (e.g. doim / doiom; pepkar; bager; kolap; nā hulu ali’i). As a strategy of defamiliarization, this jolts the visitor out of the comfortable assimilation of the exhibits to ready-made western categories, and this exhibition demands mental labour on the part of the viewer. The material is intriguing, but does this present a viable future for indigenous cultures or for the exhibition of their material culture? In many respects, it is not clear whether, in attempting to address old problems, it does not merely create new ones.

We might start with the subtitle of the show. The term ‘indigenous’ and notions of indigeneity have long been an established part of the conceptual armory of anthropology and social theory, and in recent decades the idea of ‘indigenous knowledges’ has played an important role in decolonial critiques of western science’s tendency to monopolise the space of inquiry. [11]

Yet, who is indigenous, and what is an indigenous culture? Indigenous (with an initial, capitalized, ‘I’) has been adopted by many colonized and formerly colonized peoples as an expression of political resistance, solidarity and emancipation. In this it has been taken up in opposition to older terms such as ‘native,’ which have strongly colonial overtones. Yet it is haunted by the ghosts of earlier, problematic, terms, including not only ‘native’ but also ‘primitive.’ The contemporary makers of the objects displayed in Fault Lines may not be of European ancestry, and they may have Hawaiian, Papuan, or First Nations origins stretching back centuries, yet to refer to them as ‘Indigenous’ can unintentionally reinstate the binary opposition between the (western) visitor and the (local) culture that merely reaffirms one of the most problematic divisions inherited from anthropology. Nuanced semantic distinctions can easily become lost in public political debate. Indeed, the notion of indigeneity has been appropriated by reactionary political rhetoric (e.g. ‘indigenous British,’ ‘indigenous Hungarian’) as an instrument of exclusion, in which foreigners or minorities not belonging to the majority in-group are treated as illegitimate interlopers.

Even if we try to respect the emancipatory politics of the term ‘Indigenous,’ why are works by contemporary Indigenous makers exhibited in a museum of ethnography rather than in an art museum? After all, only 300 metres away from this museum in Cambridge is the Fitzwilliam Museum, with galleries full of European artworks as well as examples of Islamic, Chinese, Indian and Japanese art. It is now common in museums of world culture to include interventions and exhibits by artists from the global South, and this is an attempt to escape from the cage of ethnography to which they are heir. Yet this practice, although well intentioned, has the unfortunate effect of boxing such artists in as continuing a tradition tying them back to indigenous origins, rather than presenting them as equal participants in the global contemporary art world.

Other issues strike the visitor to Fault Lines, too. It foregrounds the use of local languages when describing the objects being exhibited. This makes the valid point of challenging the conceptual imperialism of western cultural discourse, and it is an approach that has been widely adopted. But it might be asked at what price, for it may just lead to strengthening the impression of the exotic, alien, status of the exhibits. The maker’s statement for Ho‘oheihei reads:

When our kupuna (elder objects) leave our lands (for whatever reason), we expect for [sic] them to be cared for, respected and honoured as they would if they were home. Uwē ka pahu ho‘oulu‘ai i ka pūhā o loko (It is the hollow inside that gives the pahu (drum) of growth its cry). The pahu continually resounds, listen …

kau ‘eli‘eli kau mai, kau ‘eli‘eli ē

It is both difficult to grasp how this relates to the work on display, but also, crucially, the statement does little to help anyone other than a Hawaiian visitor understand the work, for it is rooted in a rich cultural context that remains out of sight. There is an even more baffling text on the other side of the gallery in three different languages from the Pacific North-West of British Columbia:

šxʷʔiʔtɬtən (hə’n’qəmi’nə’m: dish)

xwťlup la’thun (Hul’q’umi'num’: bowl / ‘deep plate’)

JÁU, I, (SENĆOŦEN: dish, plate)

As the English renderings indicate, these are not complex cultural concepts that remain resistant to translation (and therefore demand preservation in the original language, and the text is even more confusing by the inclusion of two different terms (it turns out that the second of each pair is the name of a specific language). This is not merely a matter of unclear labelling. Instead, it highlights a basic problem of cultural translation and mediation, to which there is no unambiguous solution. All translation is a matter of approximation, in which a term that is anchored in one cultural or linguistic system is converted to an equivalent or near-equivalent in another. In museums of world cultures, which present artefacts from radically different societies, this is much more evident than in European art museums, where, for all Europe’s linguistic diversity, there are considerably more mutual borrowings, overlappings, exchanges and cultural convergences. To confront the visitor with kau ‘eli‘eli kau mai, kau ‘eli‘eli ē or škʷʔiʔtɬtən (hə’n’qəmi’nə’m) does little to aid that process of cultural translation and, instead, serves as an instrument of obfuscation, for such terms are lifted entirely out of any linguistic or cultural context and merely emphasise cultural difference.

I have focused on Fault Lines not because it is exceptional, but precisely because it exemplifies an increasingly common approach, in which the subjectivity of Indigenous peoples is foregrounded as well as their agency, and also because it highlights the problems that can arise. One can commend this approach, especially if compared with colonial-era practices, when they were handled as merely exotic objects. Yet it is an open question as to whether it is tenable or even desirable as an imagined future, for it may end up obstructing the very process of cultural exchange it is attempting so hard to enact.

This has brought us some distance from the Náprstek Museum in Prague and the problems of the Emil Holub exhibition. What it reveals, however, is the difficult terrain currently being navigated by museums of world art and culture, and this goes far beyond the question of the provenance of their collections. The Náprstek Museum is no less affected by these issues than the more internationally known institutions in Paris, London or Berlin. The difficulty lies in the fact that these museums were created at a particular moment in time as the result of a particular constellation of circumstances and ideas. That moment in time has now passed, and formerly ethnographic museums like the Náprstek are now facing a crisis of mission and purpose. Indeed, if the example of Fault Lines is indicative of a wider phenomenon, they seem to struggle even to define their audience, how to communicate with them, or to determine why visitors go to see them. Perhaps the most uncomfortable conclusion may be the possibility that publics visit museums of world cultures precisely to see ‘exotic’ ethnographic artefacts, just as the museums in question are doing their very best to distance themselves from such ideas.

Notes:

[1] Markéta Křížová, ‘The Czech traveler Emil Holub and his African collection. Legacies of colonial aspirations and civilizing discourse,’ in MUSEA: Journal for Museology, Museum Practice and Audience 2 (2024) pp. 87–112.

[2] Emil Holub, Sedm let v jižní Africe (Prague, 1880).

[3] Viola König, ‘Under the shadow of the Christian cross: Twenty years of planning and curating the controversial Humboldt Forum in Berlin,’ in Sarah Hegenbart, ed., Curating Transcultural Spaces Perspectives on Postcolonial Conflicts in Museum Culture (London, 2024) pp. 221–244. The demand to return works of art from ethnographic museums gained a renewed momentum with the publication of Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, Restituer le patrimoine africain (Paris, 2018). See, too, See, too, Franziska Boehme, ‘Normative Expectations and the Colonial Past: Apologies and Art Restitution to Former Colonies in France and Germany,’ Global Studies Quarterly 2.4 (2022) 1-12.

[4] See, for example, Kateřina Štěpánová, Antropologie exotických sbírkových předmětů (Prague, 2016).

[5] Susan Vogel, ed, Art / Artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections (New York, 1989).

[6] Arthur Danto, ‘Artifact and Art,’ in Vogel, ed, Art / Artifact, pp. 18-32.

[7] Kendall Walton, ‘Categories of Art,’ The Philosophical Review 79.3 (1970) pp. 334-67.

[8] Walter Burkert, Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth (Berkeley, 1983) or Savage Energies: Lessons of Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece (Chicago, 2001).

[9] Shelly Errington, The Death of Authentic Primitive Art, and Other Tales of Progress (Berkeley, 1998); Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg and Peter Weibel, eds., The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds (Cambridge, MA, 2013).

[10] Fault Lines: Imagining Indigenous Futures for Colonial Collections (https://maa.cam.ac.uk/whats_on/exhibitions/fault-lines-imagining-indigenous-futures-colonial-collections).

[11] Joe Kincheloe, ed., What is Indigenous Knowledge? (New York, 2002).